History of the Guatemala

Guatemala's tumultuous history has produced a society hostile to the rights of the indigenous, yet the Maya continue to show resilience in the face of adversity. After nearly two centuries of fiercely resisting the Spanish, the last independent Mayan kingdom was incorporated into New Spain in 1697. Under the Spanish colonial government, settlement by native Spaniards (ladinos) was encouraged and the indigenous (indigenas) were forced to learn Spanish and convert to Catholicism. This binary understanding of Guatemalan ethnic identity is present to this day, with ladino culture as being "inherently superior" and Maya culture as "primitive and ill-suited for life in contemporary society" (Barrett 145). Even after gaining independence from Spain, the indigenous of Guatemala continued to suffer under authoritarian governments, culminating in a thirty-six year civil war to overthrow a US-backed dictator whose military committed acts of ethnic cleansing against the Maya (Bell 167). The 1995 agreement to end the war, the Accord on the Identity and Rights of Indigenous Peoples, promised changes in governmental attitudes towards the Maya language and culture, but contemporary Guatemalan policy is still heavily biased towards monolingual Spanish education (Bell 178).

The part that Guatemalan institutions have played in Maya language revitalization has been hampered by an ethnocentric application of language ideology. The Euro-American language ideology endorsed by the government is at odds with the traditional language ideology of the indigenous community (Barrett 144). The Euro-American language ideology is framed by linguistic nationalism, the conflation of a single language with national or ethnic identity. In contrast, the Maya ascribe to linguistic variationism, in which dialects are not “hierarchized” but instead seen as the natural outcome of “family and individual differences” (Barrett 144). The Euro-American ideology privileges the denotational function of language, or the ability of words to describe aspects of the world around us. This is at odds with the indigenous ideological perspective of language as performative, that creative speech transforms the world around them (Barrett 145). Given the ways that national institutions’ understanding of language fundamentally differs from that of their target population, it is no wonder their attempts to revitalize the Mayan language have underachieved.

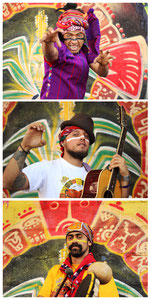

Among the first generation of Maya born since state-sponsored genocide ceased, there are many activists who are working on renewing interest in their indigenous culture in ways the government either refuses or isn’t equipped to do (Bell 168). Three such activists are founding members of the hip hop group Balam Ajpu. Balam Ajpu fuses elements of rap with their own Maya culture to produce music that both appeals to indigenous youth and raises their cultural awareness. Under the conditions of government neglect and ladino apathy and hostility (Barrett 146), Maya youth can instead find belonging in the global “Hip-hop Nation,” where citizenship is determined not by physical proximity or racial identity, but through the creation of art that reflects their cultural and political identities (Morgan 135).